How Your Clothes and Their Materials Shape Your Health

One item can lead to cancer in up to 3 out of 4 women. Another male 'essential' is tied to glaucoma and impaired brain blood flow.

STORY AT-A-GLANCE

Many dangerous chemicals end up in clothing and cosmetic products because there is almost no regulation of these products. Unless we take precautions, their toxins can enter us through our skin

Tight and constrictive clothing (e.g., ties or pants) can be particularly detrimental to health. This is best demonstrated with bras, a recent cultural invention that cause a significant number of issues. Worse still, their usage has been strongly linked to breast cancer

Sensitive patients often have significant reactions to tight or toxic clothing, providing a pivotal window into understanding this otherwise overlooked aspect of health

This article will also share the strategies for cultivating a healthy wardrobe

Years ago, a friend of mine was seated on a plane next to a chief executive of a major American chemical company that was notorious for polluting the environment and sickening large numbers of Americans with its products. After building a friendly rapport, my friend asked the executive what he considered the most important piece of advice he had to share. The executive immediately responded:

"Always wash new clothes before you put them on."

I’ve never forgotten that story, and over time, my patients have helped me appreciate how many dangerous chemicals end up on our clothing.1

The Distribution of Pharmaceutical Injuries

One of the fundamental principles in statistics is that variable phenomena tend to distribute on a bell curve, with the average value (e.g., adult American men being 5’92 — which is a bit above the global average) being by far the most common, while values become exponentially rarer as they move further away from that mean (e.g., only 15%3 of adult American men are at least six feet tall).

Sensitivity to pharmaceuticals and environmental toxins (e.g., synthetic chemicals) follows a similar pattern, with a minority of the population existing which is extremely sensitive to these things (and conversely, on the end of the bell curve, another minority exists on the opposite end which has a very high tolerance to them).

The important thing about this principle is that it can frequently allow you to infer a great deal from limited data. For example:

Shortly after the COVID-19 vaccines entered the market, I had multiple people contact me to share that a loved one had died suddenly — something I’d never seen with any other vaccine.

Given how frequently the standard vaccines cause significant injuries (e.g., the independent studies that have been done collectively show that the childhood vaccines cause between a 1.5 to 40 times increase in the rates of chronic illness), I immediately inferred that around 10% of recipients would experience significant side effects — which is insane for something being given to everyone.

Later, large surveys showed 7% of recipients believed they’d had a "major effect from the vaccine," 13.4% stated they’d developed a "severe health issue" after COVID vaccination, and 34% reported "minor effects" from the vaccine.

After Ozempic hit the market, I began seeing a large number of people with minor or moderate issues from it. Because of this, I correctly inferred serious side effects would begin emerging, especially once the higher dose for weight loss began being used.

Note: The scandalous history of Ozempic and its dangers are discussed further here.

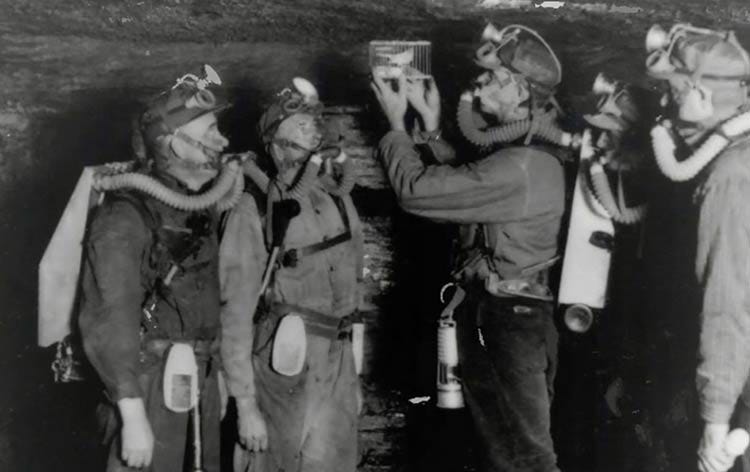

Canaries in the Coal Mine

Birds tend to be much more sensitive to environmental toxins than humans (e.g., I’ve heard numerous stories of birds dying while in the vicinity of someone cooking with a teflon pan4). This same principle was utilized by coal miners who were always at risk of a lethal toxic gas buildup (particularly of carbon monoxide) occurring in the mines.

Since carbon monoxide is odorless, they would bring canaries with them and if the canaries suddenly died, they immediately got out as they knew before long they would too.

Constitutionally sensitive patients are medicine’s equivalent of those canaries, as by being on the sensitive end the bell curve, they will immediately have significant reactions to toxins in the environment which would otherwise take a while to appreciate the danger of. Sadly, rather than be recognized, the constitutionally sensitive patients (discussed further here) are rarely recognized (rather their reactions are continually downplayed and gaslighted by the medical system).

In contrast, much of my medical knowledge has arisen from listening to these patients. For example, based on all I knew about the COVID vaccines, I thought it was mechanistically impossible for any type of shedding to occur.

However, once my most sensitive patients started asking me if other people being vaccinated could be what was making them sick and that their symptoms were remarkably similar, I knew something was happening, despite how impossible it seemed.

Since then, we’ve collected thousands of reports of shedding happening, observed it occurs in a consistent and repeatable manner, unearthed the mechanisms that explain how it’s possible and an experimental trial has been conducted demonstrating it indeed happens (all of which is summarized here).

Clothing Toxicity

As COVID-19 has shown us, the regulation of pharmaceutical drugs is deeply flawed, with financial incentives often leading to the approval and even mandating of clearly dangerous and ineffective products. However, as bad as medical regulation is, the clothing and cosmetics industry is worse, with only a sliver of oversight for what can go into cosmetics and virtually no rules for clothing.

I initially suspected there might be some issues with clothing as I found my body did not feel good in polyester clothing (e.g., when it's hot and I sweat, it often feels as though plastic fibers are coming into my skin).

Note: This may be partly due to synthetic fabrics generating positive ions.5 Excessive positive ions (or a lack of negative ions) have been linked to a variety of health conditions,6 many of which I believe are reflective of them weakening the (negative) physiologic zeta potential7 in their immediate vicinity — something critical for the body’s circulation).

Later, through discussions with colleagues and feedback from highly sensitive patients, we've established the following:

To avoid reactions, sensitive patients must wash new clothes multiple times and use fragrance-free detergents.

Reactions to synthetic fabrics are common.

While organic fabrics are an option, they’re usually only necessary for prolonged exposure, like bed sheets.

Many can’t tolerate clothing labels touching their skin.

Clothing reactions often resemble mast cell disorders,8 which are common in sensitive individuals and can be linked to other chronic conditions.

I’ve also met numerous people who react to scented products others are wearing (e.g., colognes, body sprays, or perfume). Sadly, like COVID-19 vaccine shedding, scent wearers rarely consider how their choice will affect those they encounter. This comment, for example illustrates the situation many canaries find themselves in:

Clothing Fitting

While the fabrics you wear are important, I believe the fit of your clothes is even more crucial. Tightly fitting clothing or accessories, like rings, can restrict circulation, which is especially problematic for those with chronic illnesses.

Sensitive patients often gradually choose looser clothing, likely due to impaired fluid circulation, a common issue in complex illnesses, I believe is tied to a compromised zeta potential and easily compressible vessels. I will now focus on four specific areas.

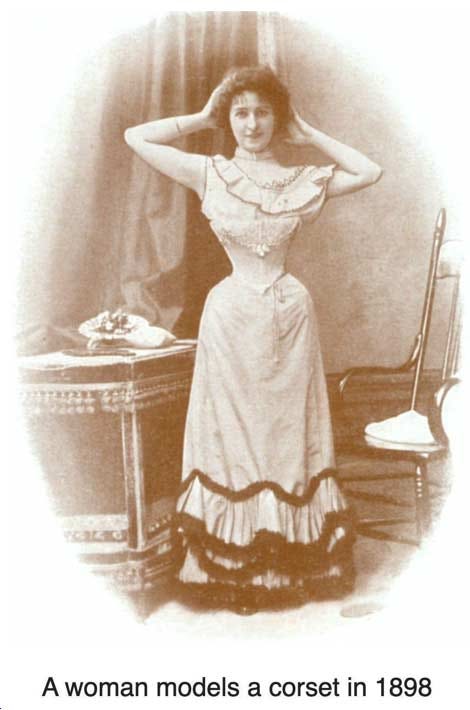

Corsets

Something most men have difficulty appreciating (let alone empathizing with) is how much pressure society places women under to conform to specific appearances that largely exist to fund the fashion industry. Consider corsets as an extreme example:

As you might imagine, wearing that was not the best thing for one’s health.9 Historically, corsets were used to shape the torso, often causing severe health issues like reduced lung capacity, organ deformities, and weakened muscles. Remarkably, a "maternity corset" was designed in the 1830s, allowing pregnant women to stay in fashion (which caused great harm to both mother and child).10

Despite these harms, societal pressure for women to conform to specific body shapes kept corsets in fashion for centuries. While it seems absurd people would do that, even today, remnants of this practice persist, with women often encouraged to compress their waists, leading to unhealthy breathing patterns.

Modern versions, like "waist trainers," continue to be popular,11 reflecting the ongoing influence of these outdated beauty standards.

Bras

Presently, Americans spend roughly 20 billion dollars a year on bras,12 which is remarkable given that prior to a century ago (the 1910s, to be precise13), almost no one wore them (whereas now between 80% to 90% of women do).

In turn, almost every woman assumes bras are something women have always worn and are not aware of the massive marketing campaign the fashion industry did to normalize this practice (which was essentially done as a pivot because they could no longer sell corsets to women).14

Since women have never worn bras for most of human history, it raises a simple question. Might there be any downsides to the practice?

Pain — Bras can cause chronic back, rib, neck, shoulder, and breast pain, often tied to restricted breathing. Many women find relief when they take their bras off, yet they continue wearing them in public due to societal expectations.

What is remarkable about this is that most women recognize this (e.g., a survey of 3000 women found that 46% of them enjoy being able to take their bras off at the end of the day,15 while another 3000 women survey found 52% take it off within 30 minutes of getting home16). During the pandemic, many women stated they stopped wearing a bra once the lockdowns allowed them to work from home and, hence, did not "need" one.17

Breast shape — There's an ongoing debate about whether bras worsen breast shape over time, potentially increasing sagging. While the evidence is limited, some like this gynecologist18 suggest that not wearing a bra could be cosmetically beneficial, challenging the marketing claim that bras maintain youthful breast appearance.

Metal allergies — An estimated 17% of women are allergic to nickel,19 commonly used in bra underwires. This can cause skin reactions, yet the industry, wishing to maximize savings, has been slow to offer nickel-free options.

Note: Nickel is found in various products like buttons, glasses, and belts, so if unusual skin symptoms appear, especially in a specific area, a nickel allergy should be considered.20

Impaired circulation — Bras compress the breasts, potentially impairing circulation and lymphatic drainage (as lymphatic circulation is very sensitive to being obstructed by external pressure). This could explain issues like headaches, indigestion, and an even higher risk of breast cancer due to lymphatic stagnation.

Breast cancer — The most controversial topic is the potential link between bras and breast cancer. While major cancer organizations deny this connection, some holistic and even mainstream sources21 argue that lymphatic stagnation,22 worsened by bras, could contribute to cancer development. Though not widely accepted, the possibility remains a point of concern.

In turn, there is some evidence to support the contention that bras are linked to breast cancer. Specifically:

A 1991 Harvard study of 9333 people23 that found "Premenopausal women who do not wear bras had half the risk of breast cancer compared with bra users."

A 1991 to 1993 study of 5000 women24 that found:

Women who wore their bras 24 hours per day had a 3 out of 4 chance of developing breast cancer.

Women who wore their bras for more than 12 hours but not to bed had a 1 in 7 risk for breast cancer.

Wearing a bra less than 12 hours per day dropped breast cancer risk to 1 in 152.

Women who never or rarely wore bras had a 1 in 168 risk for breast cancer.

For reference, this is 4 to 8 stronger than the association between smoking and lung cancer and is discussed further in the book "Dressed To Kill: The Link Between Breast Cancer and Bras."25 Furthermore:

A 2009 Chinese study found that avoiding sleeping in a bra lowered the risk of breast cancer by 60%.26

2016 Brazilian study of 304 women found women who were frequent bra wearers were 2.27 times more likely to develop breast cancer.27

A detailed 2016 meta-analysis comprised of 12 studies found wearing a bra while sleeping doubled one’s risk of breast cancer.28

Here’s my take on bras:

Try going without a bra and see how it feels. If it’s better, consider why you’re spending money and forcing yourself to wear one.

Going braless? You can conceal it by wearing thicker or looser fabrics.

Support needs — Some women, like those with large breasts, may need bras for support, but I don’t believe this applies to most women.

If you wear a bra, ensure it’s well-fitted, without an underwire, and limit the time you wear it — never while sleeping.

For daughters, encourage them to skip training bras, which have been marketed as a rite of passage by the fashion industry.

Ties

Ever since I was young, I found neckties strange, associating them with Mr. Snuffleupagus29 from Sesame Street — like having an elephant trunk hanging off you. As I began practicing, I noticed some patients seemed to develop symptoms from ties being tied too tightly, restricting blood flow. When I asked them why, they often said it’s hard to make a tie look nice without it being somewhat tight. There is also some data to support my observations. For example:

A 2003 study found that wearing a tie increased the intraocular pressure within the eyes, leading to the authors suspecting ties may also be tied to glaucoma.30

A 2011 study found neckties decreased cerebrovascular reactivity (the ability of cerebral vessels to dilate or constrict in response to challenges or maneuvers), which suggests it also impaired cerebral blood flow.31

Note: My present solution is to recommend wearing a bow tie instead, as they do not need to be fitted as tightly.

Pants

Another unfortunate fashion trend is wearing tight pants, which often cause a range of health issues. Some common problems include:

Impaired circulation — Tight pants can restrict blood or lymphatic flow to and from the legs, leading to numbness, tingling, coldness, or weakness, especially in chronically ill patients.

Vulvodynia and irritation — Tight pants can double the risk of severe vulva pain32 and contribute to microbial imbalances in the vagina.33

Testicular issues — Tight pants can compress the testicles, potentially lowering sperm count34 or even increasing the risk of testicular cancer. A study found that tight pants made men 2.5 times more likely to have impaired semen quality.35 A 2012 survey of 2000 men wearing skinny jeans found that 50% experienced groin discomfort, more than 25% suffered bladder problems, and 1 in 5 men experienced a twisted testicle.36

Nerve compression — Tight pants can compress the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, causing significant numbness, tingling, and pain in the outer thigh.37

Trusting Your Body

One of the major problems we face in life is determining how to make decisions in the face of uncertain information, especially since the funding we rely upon to create our scientific knowledge tends to be biased to arrive at conclusions that make money, not ones that promote health. In turn, as I highlighted in this article, there are a lot of simple things with clothing you would have thought would have been exhaustively studied but never actually have been.

Because of this, we often have to rely on alternative ways of knowing. One of the most reliable (but frequently dismissed ones) is listening to our bodies, which for instance, is what actually drove me to adopt the wardrobe I utilize, and similarly drove many of the chronically ill patients I mentioned above to do the same. In writing this article, I hope to encourage you to choose clothes based on how they feel, not how they look.

Note: This also applies to many other areas, such as determining the healthiest diet for the body (discussed further here). For example, I began avoiding seed oils once I realized I did not feel well while eating them, and much later, I learned all of their actual dangers.

Sadly, propaganda has effectively convinced us not to listen to our intuition so we will continue to be compliant customers.

For instance, I’ve lost count of how many heartbreaking pharmaceutical injury stories I’ve heard where the patient stated they felt apprehensive about taking the drug or vaccine, eventually agreed to take it because the doctor badgered them into it, then continued doing so once they experienced severe side effects (which their doctor told them didn’t matter), and that once they became permanently disabled, their greatest regret was not listening to their body and their intuition.

Conclusion

Being present in our immediate environment is important because it affects how we feel and live. The air we breathe, the clothes we wear, and the products we use directly impact our health. I hope this article provided some useful insights you can apply to your life, and I thank each of you for exploring the Forgotten Side of Clothing with me.

Author's note: This is an abbreviated version of a full-length article which discusses additional options for healthy clothing, cosmetics, and cleaning supplies. Please click here for the entire read with much more specific details and sources.

A Note from Dr. Mercola About the Author

A Midwestern Doctor (AMD) is a board-certified physician in the Midwest and a longtime reader of Mercola.com. I appreciate their exceptional insight on a wide range of topics and I'm grateful to share them. I also respect AMD’s desire to remain anonymous since AMD is still on the front lines treating patients. To find more of AMD's work, be sure to check out The Forgotten Side of Medicine on Substack.

Disclaimer: The entire contents of this website are based upon the opinions of Dr. Mercola, unless otherwise noted. Individual articles are based upon the opinions of the respective author, who retains copyright as marked.

The information on this website is not intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified health care professional and is not intended as medical advice. It is intended as a sharing of knowledge and information from the research and experience of Dr. Mercola and his community. Dr. Mercola encourages you to make your own health care decisions based upon your research and in partnership with a qualified health care professional. The subscription fee being requested is for access to the articles and information posted on this site, and is not being paid for any individual medical advice.

If you are pregnant, nursing, taking medication, or have a medical condition, consult your health care professional before using products based on this content.