Strength Training Turns Back the Clock on Your Biological Age

New research shows strength training slows biological aging by preserving telomeres, a factor in longevity. Discover the optimal dose of strength training here.

STORY AT-A-GLANCE

Sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss) affects many elderly people, affecting balance, mobility and independence. Strength training combats these changes by preserving and building muscle mass

Research shows telomere length, a marker of biological aging, is significantly longer in people who perform strength training. Shorter telomeres are linked to increased risks of chronic diseases and mortality

Even moderate strength training (10 to 50 minutes weekly) shows measurable benefits, with telomeres 140 base pairs longer than non-trainers, corresponding to several years less biological aging

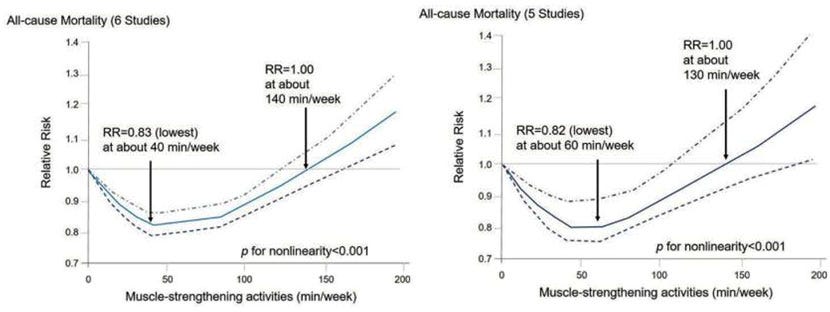

The optimal amount for strength training is 20 minutes twice weekly or 40 minutes once weekly. Exercising beyond 130 to 140 minutes weekly reduces its longevity benefits

To maximize your gains, combine strength training with KAATSU (blood flow restriction) training, which allows you to build muscle even when using light weights; make sure to also get adequate protein intake

As you get older, you naturally lose muscle, a process called sarcopenia. Sarcopenia is a leading health concern among the elderly. Research from the Alliance for Aging Research1 shows that sarcopenia affects 11% of men and 9% of women living in community settings, 23% of men and 24% of women who are hospitalized, and 51% of men and 31% of women residing in nursing homes.

Age-related muscle loss makes everyday activities harder, affecting your balance, how easily you move and your ability to live independently. Simple things like getting up from a chair or climbing stairs become real struggles. But here's the good news — strength training, also called resistance training, offers a powerful way to fight these changes.

How Strength Training Preserves and Builds Muscle

When you lift weights or do resistance exercises, you create tiny, harmless tears in your muscle fibers. Your body then repairs these tears, making your muscles stronger, a process called muscle protein synthesis. Regular strength training keeps this process going, helping you preserve and even build muscle as you age.2

Maintaining strong, healthy muscle mass is key to staying independent and enjoying a good quality of life as you get older. It boosts your metabolism, making it easier to stay at a healthy weight. It also enhances your ability to control blood sugar, which lowers your risk of Type 2 diabetes. Stronger muscles also support your bones, making them denser and lowering your risk of falls and fractures.3

Starting strength training doesn't mean you need a gym membership or expensive equipment. Simply begin with exercises like squats, lunges, push-ups and rows, which use your own body weight as resistance to engage and strengthen major muscle groups. These exercises are easily adapted to your fitness level. As you get stronger, increase the challenge by adding weights or resistance bands.

Strength Training Turns Your Body Eight Years Younger

A study from Brigham Young University,4 published in the journal Biology in October 2024, provides compelling evidence on how strength training influences biological aging by slowing cellular deterioration. The researchers analyzed data from 4,814 U.S. adults aged 20 to 69, focusing on the length of their telomeres, which are the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes.

Telomere length naturally shortens with age and is a well-established marker of biological aging, with shorter telomeres linked to increased risks of chronic diseases and mortality. Factors such as obesity, smoking, poor diet, Type 2 diabetes and low socioeconomic status accelerate telomere shortening by increasing inflammation and oxidative stress.5

The participants were also surveyed about their physical activity levels, including how often they performed strength training exercises. The researchers categorized participants into three groups based on their strength training habits — those who performed no strength training (less than 10 minutes weekly), those who trained moderately (10 to 50 minutes weekly) and those who trained extensively (60 minutes or more weekly).

Their findings6 showed that adults training for an hour weekly had significantly longer telomeres than those who did not perform resistance exercises, while even moderate strength training showed measurable benefits.

"Adults who strength trained for one hour or more per week (the highest category) had significantly longer telomeres than those who did not engage in strength training. Additionally, adults who reported some strength training, but less than one hour per week, had significantly longer telomeres than the non-strength trainers.

Men and women in the highest strength training category had telomeres that were 238 base pairs longer than those of non-lifters, and those in the moderate strength training category had telomeres that were 140 base pairs longer than those of non-strength trainers," the researchers explained.7

These results demonstrate that you don't need intense or time-consuming strength training to benefit — small, consistent efforts will still deliver meaningful results. But what does this actually mean for your biological age? According to the authors:

"[T]he findings showed that for each 10 minutes spent strength training per week, telomeres were 6.7 base pairs longer, on average. Therefore, 90 minutes per week of strength training was predictive of telomeres that were 60.3 base pairs longer, on average.

Because each year of chronological age was associated with telomeres that were 15.47 base pairs shorter in this national sample, 90 minutes per week of strength training was associated with 3.9 years less biological aging, on average. This interpretation suggests that an hour of strength training three times per week (180 total minutes) was associated with 7.8 years less biological aging."8

In other words, by adding 90 minutes of resistance exercises weekly to your workout routine, you'll be able to offset nearly four years of cellular aging, while those engaging in three one-hour sessions weekly might slow aging by almost eight years.

However, while this study demonstrates the benefits of resistance training for cellular aging, it's important to consider the broader context of exercise. Extensive or intense strength training is not something I recommend, as other research9 has shown that overdoing it significantly reduces the longevity benefits of exercise. This brings us to an important question — How much strength training is enough, and how much is too much?

The Sweet Spot for Strength Training

In my interview with cardiologist James O'Keefe, he discussed findings from his research, wherein he observed that vigorous exercise backfires, especially when done in high volumes. In fact, I radically changed my exercise program after he presented his data.

Specifically, people who were doing a total of four to seven hours of high-intensity training start losing the health benefits that exercise confers. According to O'Keefe, more is not necessarily better when it comes to lifting weights:

"I've always been a fan of strength training ... But again, the devil is in the details about the dosing. When you look at people who do strength training, it adds another 19% reduction in all-cause mortality on top of the 45% reduction that you get from one hour of moderate exercise per day.

When I strength train, I go to the gym and spend anywhere from 20 to 40 minutes, and ... I try to use weights that I can do 10 reps with ... After that, you're feeling sort of like spent and ... it takes a couple of days to recover. If you do that two, at the most three, times a week, that looks like the sweet spot for conferring longevity."

The graphs above, which come from O'Keefe's meta-analysis,10 show the J-shaped dose-response for strength training activities and all-cause mortality. As shown in the graph, the benefits max out at around 40 to 60 minutes per week. Beyond that, the benefits plateau and eventually reverse.

So why does excessive exercise reduce lifespan? Prolonged intense physical activity places chronic stress on the body, leading to issues like cardiac overuse injury and an increased risk of musculoskeletal injuries. Overtraining also impairs recovery, causing fatigue, reduced performance and a weakened immune system.11

When you're doing strength training for a total of 130 to 140 minutes per week, the longevity benefits of exercise go down to the point as if you're not exercising at all. In short, if you train for three to four hours a week, your long-term survival is actually worse than people who don't do strength training at all.

Again, when you're doing intense vigorous exercise in excess, you're still better off than people who are sedentary. But for some (yet undetermined) reason, excessive strength training leaves you worse off than being sedentary.

The lesson here is to keep strength training to 20 minutes twice a week on non-consecutive days, or 40 minutes once a week. Moreover, it's just an add-on to your exercise regimen — don't center your entire exercise sessions around it. Moderate-intensity exercise such as walking gives you far greater benefits.

Interestingly, this moderate amount of strength training aligns with findings from the Brigham Young University study,12 which showed that even small doses of resistance training — around 10 to 50 minutes weekly — result in measurable benefits to telomere length, slowing biological aging without the risks associated with overtraining.

Beyond Muscles — The Other Benefits of Strength Training for Your Body

While strength training is often used to build muscles, its benefits extend far beyond that. Like your muscles, your bones also weaken as you age. And just as strength training builds muscle, it also strengthens bones. Osteoporosis, which weakens bones and increases the risk of fractures in areas like the hips, spine and wrists, is mitigated by weight-bearing exercises.13

These exercises exert a healthy amount of stress on your bones, which makes them denser and stronger. This is based on a principle called Wolff's Law — your bones adapt to the stress you put on them.14 This leads to fewer fractures, better posture and improved mobility. Exercises such as squats, deadlifts (with proper form), stair climbing and even brisk walking are effective for bone health, and proper technique is essential to avoid injury.15 16

Beyond skeletal benefits, strength training boosts metabolism by increasing muscle mass, which burns calories even when you're resting. As you age and naturally lose muscle, your metabolism slows, making weight management more challenging.

Strength training combats this by enhancing your resting metabolic rate (RMR),17 helping your body burn calories efficiently. A faster metabolism also improves insulin sensitivity, boosting your body's ability to regulate blood sugar levels and decreasing your risk of Type 2 diabetes.18

Strength training improves balance and coordination as well,19 reducing the risk of falls, which are a major concern for older adults. This translates to greater independence and the ability to enjoy daily activities. Additionally, strength training benefits your brain, with research suggesting it enhances memory, attention and processing speed.20

By promoting the growth of new brain cells and strengthening connections between them, it protects against cognitive decline and lowers the risk of dementia.21 By incorporating strength training into your routine, you not only build stronger muscles but also strengthen bones, rev up your metabolism, improve balance and boost brain health. It's a comprehensive investment in your long-term well-being.

Boost Muscle Growth with Blood Flow Restriction Training

If you're looking to enhance your gains from strength training, consider incorporating blood flow restriction (BFR) training into your routine. I believe this is the greatest innovation in exercise training in the last century. It is also known as KAATSU in Japan, and was developed by Dr. Yoshiaki Sato in 1966.

BFR training involves the use of bands or cuffs to partially restrict blood flow to working muscles during exercise. This creates a temporary state of hypoxia (low oxygen levels), which triggers the release of anti-inflammatory myokines, which, as discussed above, promote beneficial hormonal responses and enhance muscle growth. By stimulating muscle protein synthesis, this technique significantly increases muscle mass, making it an effective tool for combating sarcopenia.

One of the standout benefits of KAATSU training is that it allows individuals, especially older adults, to achieve remarkable results without the need for heavy weights. With BFR, you'll be able to use very light weights — or even no weights at all — and still experience substantial muscle growth. This makes it a safe and accessible option for anyone intimidated by traditional strength training.

I also recommend incorporating KAATSU while doing everyday activities for added convenience. As explained in my interview with Steven Munatones, a KAATSU practitioner who mentored under Sato:

"KAATSU cycle is basically a very clever biohack that will allow the muscles to work and allow the vascular tissue to become more elastic. You don't perceive the pain of heavy lifting, but your vascular tissue and muscle fibers are being worked out just as effectively, and you can do it for a longer period of time.

Putting the KAATSU bands on your legs and walking down to the beach, walking your dog or just walking around the neighborhood, standing, cleaning your windows of your house, folding your clothes, banging out emails, all of these things can be done with the KAATSU bands on your arms or legs. You're getting the benefit of exercise.

Beta endorphins are being produced; hormones and metabolites are being produced as you're doing simple things — and that is the way to get the older population in Japan, in the United States, around the world, to understand that you can stop sarcopenia, but you have to exercise. You don't have to run a 10K, you don't have to go down to Gold's Gym. Just put on the KAATSU bands and live your life."

Protein Intake — The Essential Partner to Resistance Exercises

While strength training is important for building muscle mass, it's only half the equation. Adequate protein intake, particularly from animal-based sources, is essential for maintaining and growing muscle. Protein provides the building blocks your body needs to repair and strengthen muscle tissue, making it indispensable for achieving your fitness goals.

For optimal results, aim for your protein intake to be about 15% of your daily calories. To help you compute the specific amount, follow this guide — most adults need about 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of ideal body weight, which is your target weight, not your current weight. For example, if your target weight is 135 pounds (61.23 kilograms), your daily protein requirement is about 49 grams.

For most normal-weight adults, at least 30 grams of protein per meal is needed to stimulate muscle protein synthesis. For children, 5 to 10 grams per meal is sufficient. Additionally, one-third of your total protein intake needs come from collagen (in the example given, that would be about 16 grams) to ensure a balanced amino acid profile that supports muscle and connective tissue health.

By combining resistance training with an appropriate protein-rich diet, you build not only stronger muscles but also a foundation for better health, improved metabolism and greater resilience against disease.

Disclaimer: The entire contents of this website are based upon the opinions of Dr. Mercola, unless otherwise noted. Individual articles are based upon the opinions of the respective author, who retains copyright as marked.

The information on this website is not intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified health care professional and is not intended as medical advice. It is intended as a sharing of knowledge and information from the research and experience of Dr. Mercola and his community. Dr. Mercola encourages you to make your own health care decisions based upon your research and in partnership with a qualified health care professional. The subscription fee being requested is for access to the articles and information posted on this site, and is not being paid for any individual medical advice.

If you are pregnant, nursing, taking medication, or have a medical condition, consult your health care professional before using products based on this content.